In this post, I describe a solution to the DMCommunity May 2025 Challenge and briefly analyze different approaches to rules with exceptions and conflicts.

Other Solutions

By the time I decided to provide my solution, there had already been two solutions published : one using GenAI, and another using a regular decision table.

GenAI solution used IBM watsonx ai with Mistral. The author gave Mistral a prompt in plain English almost the same as the above problem description. For every test case, Mistral produced a solution that corresponded to the expected results. It looks like an impressive result, but I have a few skeptical thoughts: how was this solution reached? There are no explanations. Would it produce correct results when we have not 4 but 10 or 20 rules, with some of them contradicting or being exceptions to others? I am not sure about it, especially in light of the Apple research that proved that GenAI works well for relatively small instances but produces invalid results for larger instances, and such errors are quite difficult to catch.

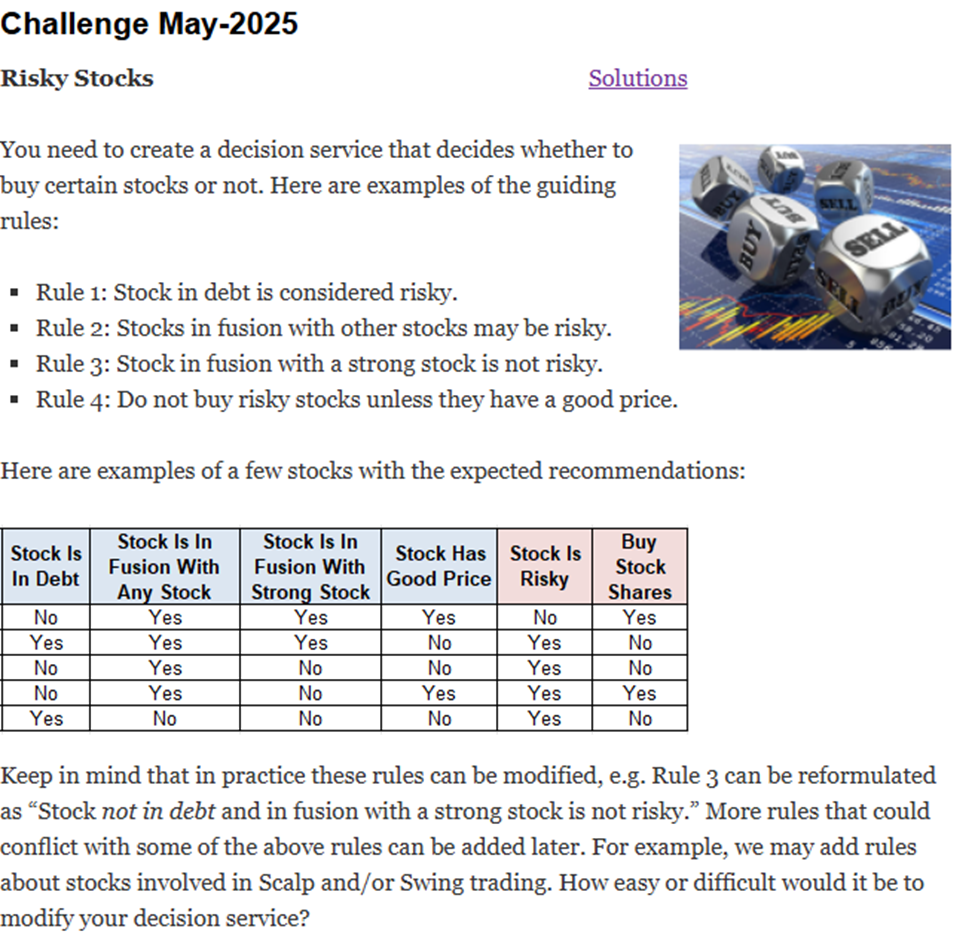

Rules-based solution used a single multi-hit decision table:

This table lists all possible combinations of 4 decision variables and relies on the order of rules that could be overridden. It also produced valid results for all test cases, and it shows the applied business logic. However, would this solution remain maintainable when we need to represent a much larger number of rules with inter-rule conflicts? When decision tables grow significantly and you still try to keep their logic dependent on the order of rules, you will inevitably hit a wall one day.

My Solution with Rule Solver

The real-world trading systems that produce buy/sell recommendations maintain many more rules – the above problem represents only a tiny business case. More importantly, these rules may be changed by financial gurus every morning and even during the day. People who have built such systems know how difficult it is to maintain those frequently changing rules, especially when they conflict with each other. Usually, such systems are rules-based and contain both hard rules and soft rules (preferences) that can be violated when necessary. I know this from experience as I was personally involved in the development of smart recommendation applications for wealth management systems for several large financial institutions.

Keeping these considerations in mind, I will share here a completely different approach that I applied to this simple challenge, but a similar approach can also be applied to much more complex real-world trading applications. When we applied a similar approach years ago, our implementation used a constraint solver and required good programming skills. This time, I will use a special OpenRules decision engine called Rule Solver. It supports Rules/Constraints with Probabilities and was designed for business analysts without programming skills.

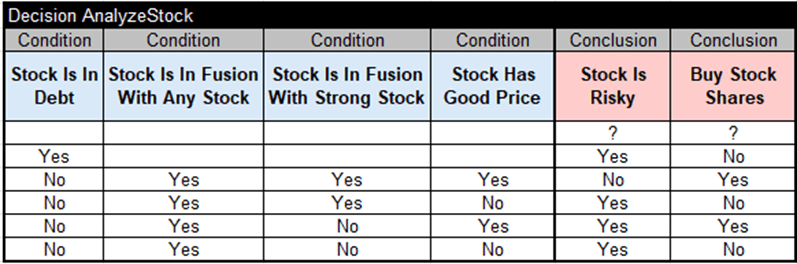

I start with the following business glossary, which is very similar to a pure rules-based approach:

It has 4 input variables and two output variables “Stock Is Risky” and “Buy Stock Shares” with possible values “1” for Yes, “0” for No.

Let’s look at the above 4 rules of the Challenge. The first 3 rules specify the conditions when a stock may be risky. Rule 4 specifies when to buy or not to buy a stock. Considering that all these rules can be expanded with more rules down the road (the Challenge mentions Scalp and Swing trading), it makes sense to create two separate decision services:

- RiskyStock1: determines if “Stock Is Risky” is true or false

- RiskyStock2: determines if “Buy Stock Shares” is true or false.

I assumed that after building the proper two decision models, I would deploy them as two loosely coupled REST services using AWS Lambda functions – OpenRules allows me to do it with one click. And then I will create one main service that will invoke these two services and implement the logical dependencies between their outputs. Such an approach may look like overkill, but it will be ready for future extensions.

Service “RiskyStock1”

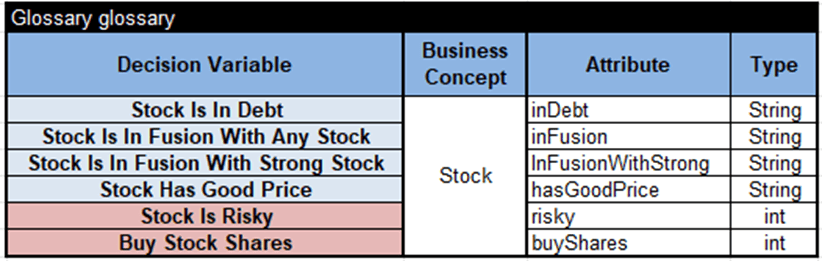

As usual for Rule Solver services, I will use two tables, “Define” and “Solve”:

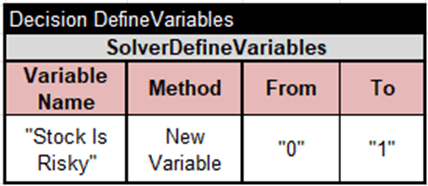

This service will use only one unknown variable, “Stock Is Risky”, with values “0” or “1”:

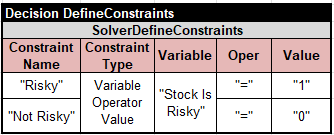

Using this variable, I can define two constraints, “Risky” and “Not Risky”:

Rules 1, 2, and 3 can be implemented in Rule Solver by posting these constraints with different probabilities:

Note that we can post these constraints in any order, and, contrary to the pure rules-based solution, they do not have to list all mutually exclusive relationships. The probability of rules/constraints defines their relative levels of importance.

Keep in mind that Rule Solver supports the following “Probability” values:

NEVER, VERY_LOW, LOW, BELOW_MID, MID, ABOVE_MID, HIGH, VERY_HIGH, ALWAYS

The probability ALWAYS means that this is a regular “hard” constraint that cannot be violated. The probability NEVER means that this constraint can never be satisfied. All other probabilities specify rules that can be violated.

When Rule Solver executes the decision model, it is looking for a solution that minimizes the total constraint violation: the higher the constraint’s probability, the more expensive its violation is. The standard method SolverFindSolution called from the table “Solve” automatically decides which constraints will be violated, making sure that the total constraint violation is minimal.

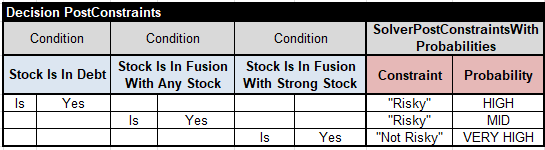

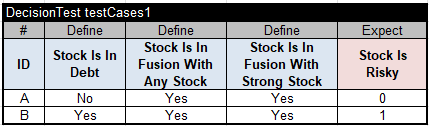

Thus, my first decision model is ready to be executed. I prepared the following test cases for my first service

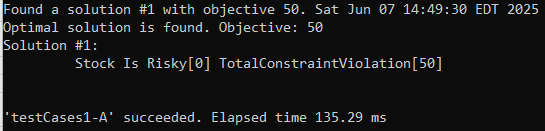

and executed this decision model using the standard “test.bat”. The produced results came as expected. Here are the execution results for Test A:

As you can see, the final (“optimal”) solution was found from the first attempt. The total constraint violation is 50, which corresponds to the violated second constraint “Risky” with Probability=MID (with an internal value 50).

To deploy this service as an AWS Lambda function, I simply executed the standard method “deployLambda.bat”.

Service “RiskyStock2”

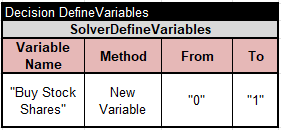

This service uses the same two main tables “Define” and “Solve” as the previous service. It needs only one unknown variable, “Buy Stock Shares”, with possible values “0” or “1”:

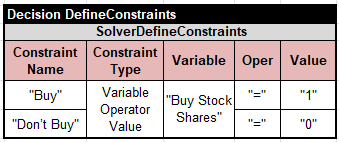

I used this variable to define two constraints, “Buy” and “Don’t Buy”:

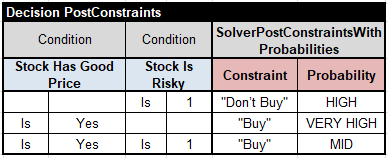

I implemented Rule 4 by posting these constraints with different probabilities:

Here, I assumed that the variable “Stock Is Risky” in the second Condition has already been defined by the previous service and came to this service as a regular input variable. This decision model is completed, and here are the test cases for its execution:

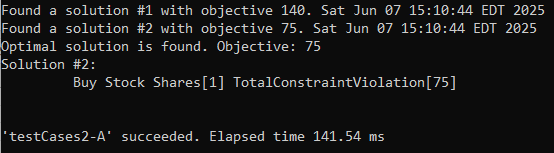

I executed this decision model using the standard “test.bat”. The produced results came as expected. Here are the execution results for Test A:

As you can see, the final (“optimal”) solution was also found from the second attempt. The total constraint violation is now 75, which corresponds to the violated first constraint “Risky” with Probability=HIGH (with an internal value 75).

Then, I again executed the standard method “deployLambda.bat” to deploy this second service as AWS Lambda function.

Main Service

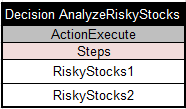

My main service uses the following simple table:

It simply executes already deployed services, RiskyService1 and RiskyService2, one after another by invoking their AWS Lambda functions. Later on, we may extend this main table by adding various conditions that analyze the results of one service before calling another service.

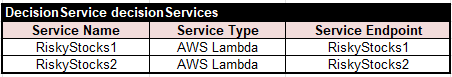

To let this decision model know about our two services, I described them in the following table of the type “DecisionService”:

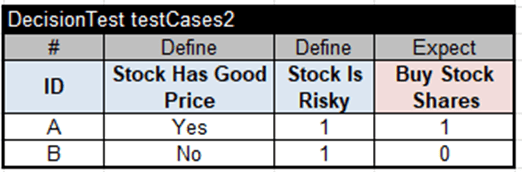

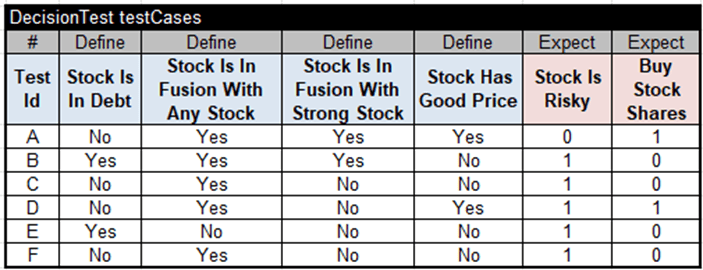

The main decision model is ready to be executed. I created the following test cases for this combined decision service:

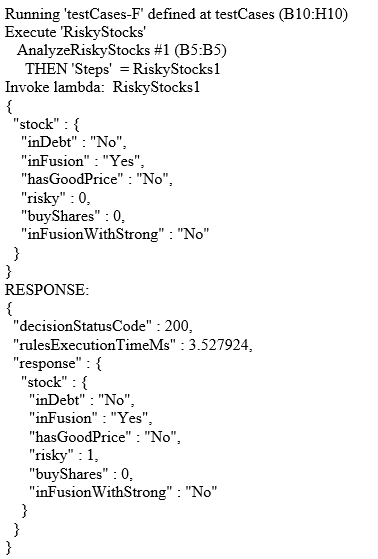

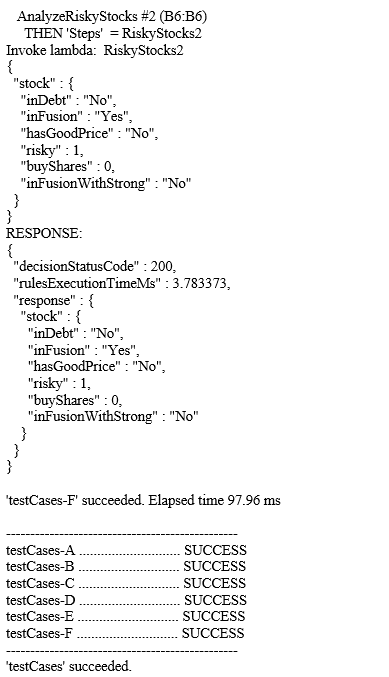

All the produced results came as expected by the Challenge. Here is the execution protocol for Test F:

CONCLUSION. This challenge contains conflicting rules. When the number of rules is small, a pure rules-based solution may look sufficiently good. However, adding more rules will complicate standard decision tables to a degree when it is too difficult to understand and maintain them. In such situations, it is more profitable to apply rules with probabilities and find a solution that minimizes the total rule violations.

CONCLUSION. This challenge contains conflicting rules. When the number of rules is small, a pure rules-based solution may look sufficiently good. However, adding more rules will complicate standard decision tables to a degree when it is too difficult to understand and maintain them. In such situations, it is more profitable to apply rules with probabilities and find a solution that minimizes the total rule violations.