“When it comes to AI, expecting perfection is not only unrealistic, it’s dangerous.

Responsible practitioners of machine learning and AI always make sure

that there’s a plan in place in case the system produces the wrong output.

It’s a must-have AI safety net that checks the output,

filters it, and determines what to do with it.”

Cassie Kozyrkov, Chief Decision Scientist, Google

“When we attempt to automate complex tasks and build complex systems, we should expect imperfect performance. This is true for traditional complex systems and it’s even more painfully true for AI systems,” – wrote Cassie Kozyrkov. “A good reminder for all spheres in life is to expect mistakes whenever a task is difficult, complicated, or taking place at scale. Humans make mistakes and so do machines.”

Like many practitioners who applied different decision intelligence technologies to real-world applications, I can confirm the importance of this statement. I also can share how we dealt with the validation of automatically made decisions in different complex decision-making applications.

Can we trust the results produced by a very sophisticated decision engine? This crucial question has always been on the minds of people who developed and used complex decisioning systems years before Generative AI came to light. The notorious AI “hallucinations” bring attention to the necessity of sanity checks, but any complex automated systems could produce erroneous results by human mistakes or when dealing with unexpected situations. How did we usually deal with such mistakes? We put in place Sanity Checkers (manual or automated) to evaluate whether the result of a complex calculation is true or false and how to correct it when necessary. I will provide you with a few examples of sanity checkers in real-world applications I dealt with in my multi-year career as a developer of complex decisioning systems.

Example 1 (Manual Sanity Checkers). Many years ago, I was involved in the development of a gas network optimization system that was able to find optimal diameters for gas pipelines based on streams, required pressures, corrosion levels, etc. Our system managed to do it in hours while it took months for the highly trained engineers to do it manually. And our results tended to be optimal. However, the same engineers didn’t trust our automated system. So, they always visually validated the produced decisions: in most cases, they liked some of them and were upset about the others. For instance, they noticed that our system recommended switching from a small diameter to a large one without respecting the so-called “telescopic” constraint. As we allowed them to manually assign diameters, they “froze” some diameters using their understanding of the pipeline and let our system choose unfrozen diameters by running it again. Through such sanity checks after several runs, they managed to essentially improve the final decision, and we usually witnessed an additional saving. Of course, finding such errors helped us to gradually advance our system, but those human sanity checkers remained an essential part of the pipeline design process even after our system was in production for years.

Example 2 (Automated Sanity Checkers). In the 1990s I was involved in the development of complex optimization engines for large US and Canadian corporations using the great Constraint Solver from ILOG. Usually, these systems were quite complex and required the implementation of custom constraints and heuristics to make these large decision-making applications efficient. As a few examples, I can mention scheduling and resource allocation engines we developed for these companies: 1) Long Island Lighting Company to make the best assignments of teams of workers to various gas and electric jobs; 2) CP Rail to build and schedule multiple local and mainline trains that should pick up grain from different locations over the entire Canada and delivering it to the two major Canadian ports.

The resulting decision engines were quite complex and required deep knowledge of the underlying technology to understand how they worked. After serious testing, the systems were ready for production and demonstrated good performance and better than manual results. However, the companies wanted to make sure that the produced results really satisfied all their requirements and constraints when running against production data. It was too difficult to do it manually. To win customers trust, we developed automated rules-based Sanity Checkers. They were implemented as relatively simple rule engines that took the results produced by the scheduling engines and ran them against various business rules to check satisfaction of major constraints (e.g., a person assigned to the job has the skills to do it, or trains arrive at certain stations giving enough time to be loaded, unloaded, and/or reattached to a different locomotive). It was really important that these sanity checkers implemented validation logic in business rules created and maintained by SMEs (subject matter experts who were not programmers). These rules were completely understood by them and as a result, they trusted that the produced decisions did not violate the requirements expressed in their rules.

Building rules-based sanity checkers became quite common to validate the results produced by complex optimization engines which remain “black boxes” for business users (SMEs) who wrote the validation rules. If we replace optimization engines with decision engines produced by Generative AI they similarly will be “black boxes” for SMEs, and the need for Sanity Checkers to whom they can trust will only grow.

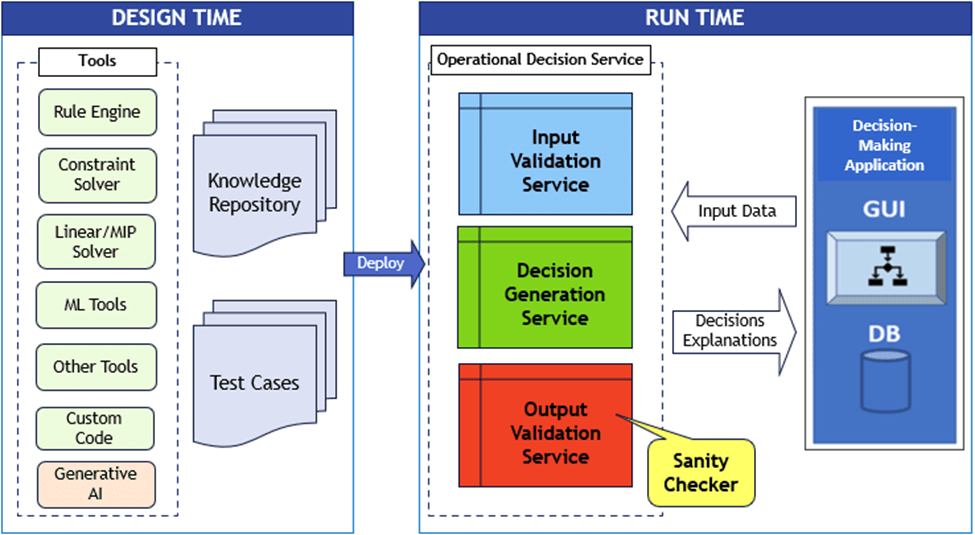

Let’s go back to today’s decisioning systems. The following architectural schema summarizes how a complex decision service worked then and can work now:

RUN TIME. The operational decision service usually orchestrates 3 other services:

- Input Validation Service

- Decision Generation Service

- Output Validation Service (Sanity Checker!)

Here we are talking about decision services that are applied to automate repetitive day-by-day problems in real time. In many cases. they are supposed to handle hundreds of thousands and even millions of complex transactions per day. So, we assume that all these services have been already deployed on-premises (like years ago) or on-cloud using modern CI/CD frameworks. We will not talk here about decision services capable of learning in real-time.

The first service “Input Validation Service” validates input data and if necessary, calculates more data required by the “Decision Generation Service”. If there are errors in the input data, the negative results will be returned to the decision-making application with explanations of the errors. It is only natural to implement the first service “Input Validation Service” using a rules-based decisioning tool. If there are no errors in the input data, the second service “Decision Generation Service” will be called with positive results from the first service.

The second service “Decision Generation Service” is the one that executes the main decisioning logic. Independently of which technology was used to implement and deploy this service, the main objective is to use input data to produce the expected decisions with necessary explanations. Of course, this service may invoke other loosely coupled decision services.

The third service “Output Validation Service” validates the produced decisions and based on its validation logic comes up with positive or negative results returned to the decision-making application. This service implements the Sanity Checkers we discussed earlier and we again can use any off-the-shelf rule engine for its implementation.

DESIGN TIME. The Operational Decision Service used in RUN TIME is usually created, tested, and deployed during DESIGN TIME when it’s usually called the Decision Model. Its two major components are:

- Knowledge Base which represents business logic in the executable format.

- Test Cases that are used to make sure that the produced decisions are the same as expected.

The decision model can be implemented using different decision intelligence technologies including:

- Rule Engine: supports user-friendly representations of business rules

- Constraint Solver: for representation of constraint satisfaction and optimization problems

- Linear/MIP Solver: for superfast solving of linear and mixed-integer optimization problems

- Machine Learning tools: such as RuleLearner capable of learning rules from data

- Other Tools: such as Probabilistic Reasoners

- Custom Code: written in any programming language

- Generative AI tools: capable of generating specialized decision engines based on the existing documents (LLMs) and human prompts in the natural language.

Of course, concrete decision models may utilize different techniques, tools, and their combinations (e.g. look at an integrated use of Rule Engines and Constraint Solvers for declarative decision modeling). Being used independently or in combinations, these tools provide a great foundation for creation of powerful decision model and services. However, as we stated above, even the best decision models still may produce mistaken decisions and that’s why a Sanity Checker should be a part of any decision service.

P.S. Just read the related article “The promising alliance of generative and discriminative AI“: “While generative AI creates something new, discriminative AI determines if something is correct. “